If you know me or have been reading this newsletter for any length of time, you may know that photography is my favourite pastime. What you may not know is that organizations sometimes bring me in to take photos of their events, which is how I found myself at the AllerGen 2012 Annual Research Conference.

AllerGen is a not-for-profit organization whose role is to mobilize Canadian science to reduce the illness, mortality and socio-economic costs of allergic disease. The conference showcased the latest research in this regard and while often over my head scientifically (not hard to do), I found it quite interesting.

During an afternoon break at the conference, a distinguished looking gentleman named Douglas Barber approached me to talk photography. Our pleasant conversation eventually shifted to the conference and he told me a story that I quickly realized fit my thinking on marketing measurement.

Douglas explained he is on AllerGen’s board and that an issue of concern to him is the cost to the Canadian economy from the “asthma drag” on productivity. He explained how asthmatics can be less productive at work or even miss entire days of work following sleepless nights caused by asthma. Parents of asthmatic children can also experience the same productivity losses. Douglas also told me how he once did a quick “back of the envelope” calculation to estimate that asthma costs our economy between $10 and $20 billion per year in lost productivity.

Sometime after Douglas did his quick calculation, a full study was done to properly analyze and estimate the economic impact of asthma’s drag on productivity. The study concluded the annual costs are $15 billion. That’s right; a costly and complex measurement process produced the same answer as one expert using a pen and the back of an envelope.

Two aspects of this story relate to my views on marketing measurement:

- Douglas’s back of the envelope calculation relative to the full study is similar to how a marketing scorecard can be a proxy for a sophisticated and costly marketing measurement process. In both cases, the less sophisticated approach doesn’t need to be perfect, just accurate enough to support analyzing options and making the right decisions. As I like to say, it’s not about precision, it’s about the decision.

- The back-of-the-envelope estimate worked because it was done by an expert using a sound methodology. Douglas has an extensive business background and apparently knows more than just a little about productivity and related calculations. Scorecards are a proven methodology that you can enhance with expertise about your marketing and your business.

There is another lesson in Douglas’ story, and that’s the need to right size your measurement efforts to the magnitude of the decisions you need to make.

Research Investment Decision

- Douglas’ back of the envelope calculation and the full-blown study produced essentially the same estimate and both pointed toward making the same decision. It’s a pretty compelling proposition if investing perhaps a few hundred million dollars into research would lead to recovering even just 10%, or $1.5 billion of the lost productivity, especially as that benefit would be realized every year.

- The problem is that any decision to potentially invest a few hundred million dollars needs to be substantiated by more than a back of the envelope calculation. In this case, the cost of the research needed and the probability of recapturing that 10% are two other variables that I think would need to be estimated. It’s understandable that a full-blown study was needed to examine the overall business case.

Marketing Investment Decision

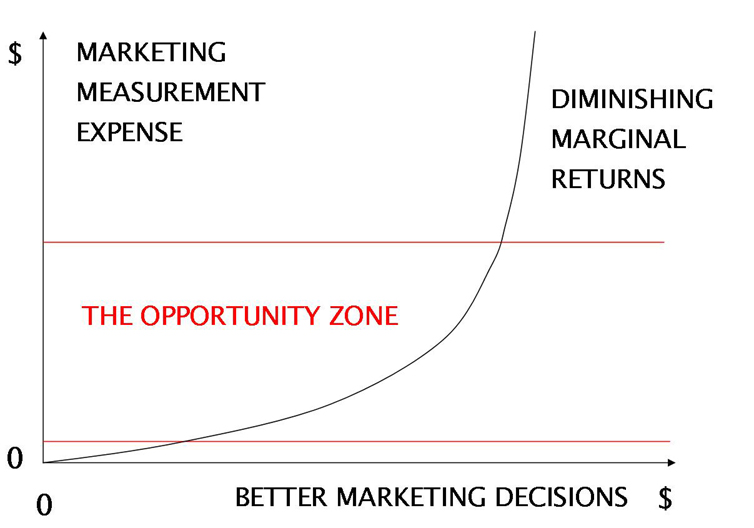

- Similarly, for companies that invest tens of millions annually in marketing, it makes sense to support the decisions that need to be made with sophisticated marketing measurement efforts that might cost hundreds of thousands, or more.

- For most companies with smaller marketing budgets, a practical lower cost approach such as one using a scorecard may well be the right sized measurement solution. In most cases, the overall measurement expense likely needs to be a small single digit percentage of the total marketing budget.

I like simple and elegant solutions that deliver what you need. A marketing scorecard’s simplicity keeps measurement costs down, while its elegance allows the flexibility to include a suitable level of expertise and sophistication to right size your measurement efforts to your marketing budgets.

Whichever measurement approach you choose, be sure to combine a sound methodology with the right expertise to learn what you need to know to make the right decisions. Measuring well will help you to sleep well and be a productive marketer!