Megan Kalmoe rowed for the United States at the Beijing Olympics and is a 2011 World Silver Medalist. While she’s obviously a great rower, I hadn’t heard of Megan before reading Randy Starkman’s article in the Sports section of the Toronto Star on October 13, 2011.

The story focused on the fact that Megan named two Canadian men to the 2011 edition of her “20 Hottest Male Rowers” list, which she recently published on her blog. Not surprisingly, I didn’t make the list. One reason is that I’ve never rowed in my life. There might be other reasons, perhaps many, but more on that later.

I’m happy when Canadians do well in any international ranking, but being a marketing measurement guy, my interest in this article was to learn about Megan’s rating and ranking process.

Here’s what I learned:

- You must be a world class male rower

- You may lobby Megan to get on her list

- Megan’s female friends can nominate you and lobby on your behalf

- If Megan thinks you’re hot, she might add you to the list

As far as I can tell, Megan’s approach is pretty subjective and unstructured, and the resulting list reflects her opinion, which is fine. I can’t tell whether lobbying influences Megan’s decisions, but it really doesn’t matter.

It is worth noting that Megan is just having fun with this and important strategic decisions aren’t being made because of her list. But, consider this. What would happen if the top three rowers on Megan’s list landed endorsement deals because they topped her list?

I think the fun and friendly lobbying might get a little more intense for the 2012 list, and Megan might feel the need for a more structured approach to minimize the impact of bias and personal opinion on the rankings.

For now, since this is all in good fun, Megan’s methodology for measuring male rower hotness is perfectly appropriate and as good an approach as any. However, when it comes to measuring marketing program hotness, marketers need a more rigorous approach.

What if you used a similarly unstructured method for measuring marketing programs? Brand managers would lobby you to have their programs highly rated. People working in sales, finance, customer service or operations would also offer their opinions. You wouldn’t have much fact-based data and you’d end up having to make an opinion-based judgment call.

The impact on your judgment call of everyone lobbying to influence your opinion might come down to:

- The clout of each person doing the lobbying, perhaps related to their role in the organization

- Each lobbyist’s communication skills and powers of persuasion

- Your ability to separate fact from opinion, and to somehow remain objective

Here’s the problem. You don’t want the most effective lobbyists to skew the rankings in their favour. Nor do you want personal opinion and bias tainting your overall approach. Opinions are interesting, but not very actionable.

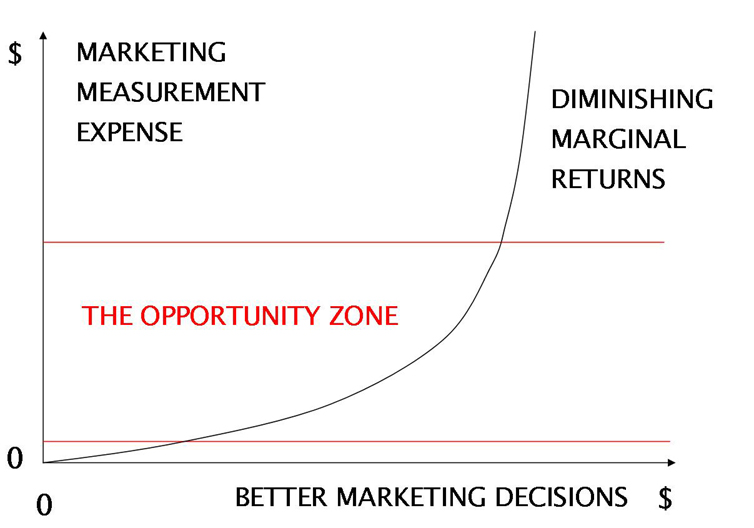

To be able to take action, make good decisions and adjust strategies, you need data to identify your most and least effective programs. A structured and disciplined methodology will give you that data, while filtering out opinion.

To remove as much personal bias and opinion as possible from your marketing measurement efforts:

- Involve the Right People: Create a cross-functional group to pick an approach that balances everyone’s needs and interests, so the approach is fair and equitable for all.

- Involve Unbiased People: People with no vested interest in which programs get the highest rankings could include an analyst, someone from Accounting, or an independent consultant.

- Set Clear Evaluation Criteria: Disclose how you will consistently evaluate each program, so everyone knows and plays by the rules.

- Set Objectives Up Front: This prevents people from later setting lower objectives than they would have up front, thus making both their successes and failures look better.

Whether you need to identify your 20 hottest marketing programs, or which types of marketing spending should be increased or decreased, make sure your measurement methodology gives you the unbiased and opinion-free data and facts you need to make better decisions.

As for the fact I didn’t make Megan’s list, I think if I was at least 20 years younger, 10 pounds lighter, 5 times as athletic, a lot hotter and a world class rower, I could have been a contender. Of course, Megan might have had a different opinion!