Introduction

As content marketing grows in importance, it is worth questioning and measuring how engaged your audience is by your content, and whether they are engaging in the way you would like. This post outlines a practical approach to answering this question.

First words are magical moments. You may not remember the exact moment when you spoke your first word, but I expect your parents remembered and told you what you said. What was your first word?

My parents happily told me many times that my first word was “light”, although I suspect they secretly would have preferred something closer to “mom” or “dad”.

Can you imagine a more engaged audience than parents listening to their child’s first words? They engage fully in the whole experience; from their encouragement in the lead up to the first word, to the excitement of the moment and the pride that follows. That’s an engaged audience. That’s why they remember your first word.

Of course, the relationship between a business and its customers is rather different, and customers will tend to be considerably less engaged than parents. Still, as content marketing grows in importance, the question you need to ask is: “How engaged is your audience by your content?”

On the continuum of engaged audiences, on a scale from 0 to 100, most parental audiences are 100% engaged. When I develop marketing content, for myself or for my clients, I hope to engage my audience on the higher end of the scale, and so should you. It’s a lofty ambition, and I expect to fall a little short, but it’s better than the other end where no one reads, cares or reacts.

So, how do you measure where your audience is on the engagement scale? Well, it helps to have a scale to answer that question. Here are four steps to developing your scale, with the first step being:

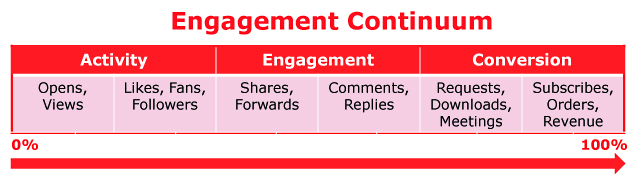

1. Define Your Engagement Continuum

Start by defining a general continuum for outcomes related to your content marketing activities, keeping in mind their relevance to your overall business objectives. There isn’t necessarily one right way to do this and you don’t need to assign numerical values to everything between 0 and 100%.

The main point is to think about the engagement objectives of your content marketing in ascending order of importance. What do you want your audience to do? Which outcomes are most helpful in meeting your business objectives? Defining your engagement continuum will help you to have greater clarity about what you are trying to achieve with your content and how you define success.

The main point is to think about the engagement objectives of your content marketing in ascending order of importance. What do you want your audience to do? Which outcomes are most helpful in meeting your business objectives? Defining your engagement continuum will help you to have greater clarity about what you are trying to achieve with your content and how you define success.

Thinking about how your prospects engage with your content is similar to how we might think about how prospects engage with us in a sales funnel, with Opens and Views being top-of-funnel activities, leading down through to the preferred conversions at the bottom of the funnel, such as Subscribes or Orders.

Then, you can adjust your continuum for each specific content marketing program or initiative. For some programs, the hoped for conversion might be a sale to an existing customer, or to a new customer. In others, the program objectives might relate more to building an audience or moving prospective customers along the path to purchase, and generating quality leads.

Defining your Engagement Continuum ties directly to the second step:

2. Define Your Metrics

Your metrics are the units of measurement on the engagement continuum. As I’ve written about previously here, I like to organize metrics into three groups, Activity, Engagement and Conversion, which also fit logically along the engagement continuum.

The simplest activity metrics, such as opens and views, can lead to early signs of engagement, through counts of likes, fans and followers. The more engaged audience goes beyond those activities to share, forward and comment on your content.

The very engaged might convert to requesting more information or downloading something. Ideally, they will purchase something, or refer a new customer to you. For some content, your objectives might be to gain more subscribers or registrations for something.

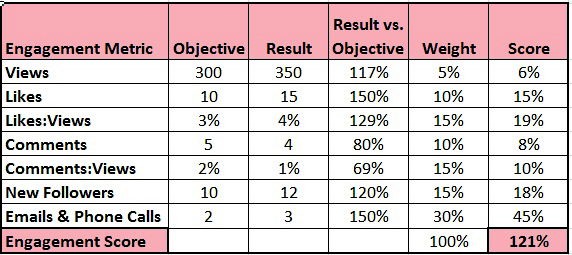

Let’s consider metrics for this post, as an example. LinkedIn provides data on three metrics related to each post: Views, Likes and Comments. I track how many Followers I add as a result of each post. I also note the number of emails or phone calls I receive from prospective clients, triggered by each post.

To those five metrics, I add two engagement ratios, which normalize my data and give me a sense of which pieces of content have been most effective at engaging the audience that actually saw my content. In this case, I’ll create ratios for Likes as a % of Views, and Comments as a % of Views.

That gives me a total of seven metrics that help me to understand if my content is engaging my audience. The third step involves scoring my results for those metrics.

3. Score Your Results

To give meaning to your metrics, you need to be able to answer the question “How good is that number?” Scoring your result takes you from merely counting, to measuring.

Continuing with my example above, now that I have seven previous LinkedIn posts under my belt, I can compare each of my seven engagement metrics for this post to my averages for those same metrics on my previous posts. I could also compare it to the averages of similar posts by other publishers on LinkedIn.

Ideally, the results of any marketing initiative should be compared to a corresponding set of objectives. I could use my averages as my objectives, but I’ll generally put a bit of stretch into the objective by aiming higher than my averages. I score my results by expressing them as a percentage of the objective.

For example, I’ve averaged around 250 views for each of my first seven posts. Rather than set an objective of 250 for this one, I’ll set it at 300. If I end up getting 350 views, then my score on that metric will be 350/300 X 100 = 117%.

Now it’s time to put all seven of my scores on a scale.

4. Create Your Scale

Given that your metrics will likely vary from program to program, you will need a flexible way to score and total your results for the range of metrics associated with each program.

For that, I advocate using a standardized scorecard that will accommodate the diverse audience engagement data that you’ll collect for each program. Using a consistent scorecard methodology for measuring audience engagement for each post gives me a way to rank my posts. That ranking helps me to learn what type of content seems most relevant to my audience, and the ability to act on that knowledge and hopefully create more engaging content.

Some metrics are more important than others. So, weight the metrics on your scorecard according to the importance you’ve assigned them by where you placed them on the engagement continuum. Conversion metrics should be weighted higher than Engagement metrics, with Activity metrics weighted lower than the others.

Your scorecard gives you an easy way to total up the weighted scores for each metric as you compare each result to its objective. Below is a simplified example of a scorecard that I use to score each post.

Summary

It’s nice to think that your audience is parentally engaged, waiting for your next piece of content with great anticipation and hanging on your every word as they read, listen or watch. While that is highly unlikely, it is worth trying to understand which pieces of content come closest to that ideal, so you can focus on creating more of that kind of content.

Creating good content takes time and effort, so you might as well put in a little additional effort towards measuring and understanding whether you’ve succeeded at engaging your audience.

As with most marketing measurement exercises, your science will be inexact. However, if you apply your measurement efforts in a consistent and disciplined manner, your measurement results will be directional enough to help steer you towards better decisions that focus and improve your content marketing activities.

If I’ve engaged you enough that you’d like me to send you an excel file with the above example of an Audience Engagement Scorecard that you can customize for your own use, please email me and I’ll happily send it to you. Of course, I’d appreciate it if you could share this post with any individuals or audiences you feel might also like to be engaged!